A recent thread in Roobarb’s, one of the relatively sensible cult TV forums, was headed “Fifty years of grumbling – why do we love Doctor Who so much?” And it’s true that fandom of Doctor Who – or any cult show – can often feel very negative. One of the definitions of a ‘cult’ TV series is that it is of interest to its fans over and above its role as a TV series: that is, fans don’t just care what happens next, they care how it is made and who’s involved. When the show is great, they feel happy and proud beyond the normal enjoyment of enjoying a bit of TV; when the show lets them down, it’s painful. So a lot of what has happened this year regarding Doctor Who has mattered a lot to a lot of people – more than it rationally should. This is my take on ten of the things that have gone on.

A recent thread in Roobarb’s, one of the relatively sensible cult TV forums, was headed “Fifty years of grumbling – why do we love Doctor Who so much?” And it’s true that fandom of Doctor Who – or any cult show – can often feel very negative. One of the definitions of a ‘cult’ TV series is that it is of interest to its fans over and above its role as a TV series: that is, fans don’t just care what happens next, they care how it is made and who’s involved. When the show is great, they feel happy and proud beyond the normal enjoyment of enjoying a bit of TV; when the show lets them down, it’s painful. So a lot of what has happened this year regarding Doctor Who has mattered a lot to a lot of people – more than it rationally should. This is my take on ten of the things that have gone on.

All in all, it’s undeniably been a good year to be a dedicated Doctor Who fan, particularly for veterans of the 90s wilderness years, who should be able to get even the negatives into perspective. What’s more debatable is whether it’s been a good year to be a keen regular viewer of Doctor Who. But let’s start with the good stuff…

The Day / Night / Time of the Doctor

In many ways it now seems that the entire Matt Smith era has been constructed by Steven Moffat to lead up to the 50th anniversary special and subsequent Christmas special. Moffat stated at the time of Matt Smith’s departure that three series plus these two specials was always the plan, albeit that he tried to persuade Matt to stay longer – this certainly explains the decision to spread out the 2012 series across two years, as the alternative would have been to go into the fiftieth anniversary year with a new and untested Doctor, which would undeniably have been a high risk plan.

In many ways it now seems that the entire Matt Smith era has been constructed by Steven Moffat to lead up to the 50th anniversary special and subsequent Christmas special. Moffat stated at the time of Matt Smith’s departure that three series plus these two specials was always the plan, albeit that he tried to persuade Matt to stay longer – this certainly explains the decision to spread out the 2012 series across two years, as the alternative would have been to go into the fiftieth anniversary year with a new and untested Doctor, which would undeniably have been a high risk plan.

Taking the specials as a package with the three series before them, they’re an impressive run of sci-fi storytelling of the sort that one normally associates with American shows. The Christmas finale did indeed tie up the outstanding plot points from the previous series, as well as resolving the “twelve regenerations” problem, for the next few decades at least. It met with a markedly mixed reaction though – Roobarb’s was utterly split on it, which is very unusual as normally it’s very warm towards the new series, and I gather it got the show’s lowest audience appreciation index figure since 2006. Perhaps it didn’t add up to much beyond the resolution of existing plotlines and catalyst for a regeneration – there was little to it beyond those aspects, and the fact that it stood alone rather than coming at the end of a series that had been building to it maybe meant that approach worked a bit less well than it might have done. As a finale to an era though, I thought it was great – anyone watching the whole Smith run as a boxset binge will find it a satisfying ending.

Far less difficult was The Day of the Doctor, which was superb. Yes it had its fanwank elements – a new ‘secret’ Doctor, the time war business – but an anniversary special will inevitably delve into the mythology. David Tennant gave one of his best performances as the Doctor, and his interplay with Matt Smith was great. It also managed to have a convincing epic feel while ultimately being character-driven and still light enough to remain watchable throughout. In one of the online quasi-Confidential videos, Moffat remarks that it’s with scripts like this that he really earns his money, and he’s not wrong – it’s hard to see what other writer could have delivered such a rich yet nimble script for the anniversary.

Finally, Paul McGann’s on-screen return in the mini-episode The Night of the Doctor was very well deserved. Through his audio performances for Big Finish he has proved himself an accomplished Doctor (indeed, his audio adventures alongside Sheridan Smith’s Lucie Miller count as some of my favourite Doctor Who in any medium), and his lovely turn here really underlines how we were robbed by the failure to make a series starring him (though if it had come from the production team behind the TV movie, unfortunately it would probably have been pretty ropey).

Overall the episodes of November and December did a great job of celebrating the show, rounding off an era and setting Doctor Who up for the future. Very well done.

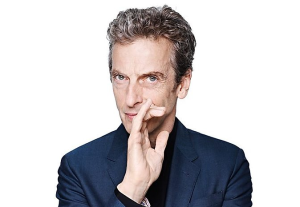

The casting of Peter Capaldi

I shouted “yes!” out loud and I know I wasn’t alone. It still seems hard to believe that such an accomplished actor would come to Doctor Who with such a great career behind him, so little to prove and, really, so much at stake should it go wrong. But on reflection it does make sense: Capaldi is now relatively late into his career (not all that late of course, one hopes), yet he’s never had a truly household name type role – yes, there’s Malcolm Tucker, but that’s very much post-watershed and ultimately The Thick of It remains a relatively niche interest show. Breaking the Tucker association and taking on such a popular role, rather than representing a risk or step back for Capaldi, could crown his career. Word is that Moffat also plans a shift of tone for his era, the key word being gritty rather than fairytale, so it should be exciting.

I shouted “yes!” out loud and I know I wasn’t alone. It still seems hard to believe that such an accomplished actor would come to Doctor Who with such a great career behind him, so little to prove and, really, so much at stake should it go wrong. But on reflection it does make sense: Capaldi is now relatively late into his career (not all that late of course, one hopes), yet he’s never had a truly household name type role – yes, there’s Malcolm Tucker, but that’s very much post-watershed and ultimately The Thick of It remains a relatively niche interest show. Breaking the Tucker association and taking on such a popular role, rather than representing a risk or step back for Capaldi, could crown his career. Word is that Moffat also plans a shift of tone for his era, the key word being gritty rather than fairytale, so it should be exciting.

Also, for all the moaning that they’ve cast another white man, let’s not overlook the significance of casting someone of Capaldi’s age: if he does the now-traditional three years plus specials to stretch his run to four, he’ll become the oldest actor ever to play the part (he’s already the oldest since 1974) – and the online reaction from younger fans shows that having a mature actor in the part is a big deal, perhaps more so for some than casting a woman, for instance, would have been.

The departure of Matt Smith

Well the rumours were swirling from early in the year, and I (sadly, in many ways) drew the conclusion that Matt was on his way some time before Ian Levine spilt the beans and forced the BBC into a rush announcement. While three years plus specials now looks like the standard deal, it’s really not all that long – a fourth full series from both Tennant and Smith would probably have been better. As it was, I was left wanting more both times – but maybe that’s the skill.

Well the rumours were swirling from early in the year, and I (sadly, in many ways) drew the conclusion that Matt was on his way some time before Ian Levine spilt the beans and forced the BBC into a rush announcement. While three years plus specials now looks like the standard deal, it’s really not all that long – a fourth full series from both Tennant and Smith would probably have been better. As it was, I was left wanting more both times – but maybe that’s the skill.

If anything, I felt Matt’s performance surpassed David Tennant’s (minority view, I know): he brought a more marked off-beat, alien tone to it – as Moffat has remarked, despite being the youngest actor in the role, he took it back to the ‘eccentric scientist’ aspect first envisaged for it in the sixties, and really did convince as an old man in a young man’s body. Both he and Tennant got a bit bigger and more shouty in their performances towards the end of their eras – a reflection of the writing as well as their own instincts – and I preferred their earlier more reflective performances. One nice thing is that Matt seems to have been turned into a fan by being on the show, the first time that’s really happened; he’s been, and will surely remain, a great ambassador for the series as well as a great lead actor.

Doctor Who

If there’s been one less rewarding aspect of the anniversary year, it’s been Doctor Who. By which I mean that the series itself, outside the anniversary and story arc hoop-la, seemed to be firing on slightly less than all cylinders. As mentioned, I think the reason for the low episode count was almost certainly to eke out Matt Smith’s tenure to include the anniversary rather than because of any other rumoured cause – a falling-out between Smith and Moffat, a greater focus from the latter on Sherlock, budgetary problems and so on. That said, the rumours around Caroline Skinner’s undeniably sudden departure didn’t sound at all good, and were leant credence by an abrupt end to her high profile in promoting the show informally via Twitter.

A more meaningful problem was the decision to swing away from series six’s heavy arc-based approach by making every episode of series seven a single, stand-alone story. Ever since the show came back it’s been clear that a single 45-minute episode can be a hugely powerful format for Doctor Who, but the best have often been the smaller-scale stories (Blink, Midnight and Turn Left spring to mind – the latter grand in scope in some ways, but clearly focused on a single character more than what’s going on around her). The idea of each episode being a mini-movie in its own right led to lots of attempt at creating scale, usually successful… but at the cost of some very thin plot – when all’s said and done, 45 minutes is only 45 minutes, and there’s a reason most films are 90 or more: creating a whole world and satisfying story usually takes quite a bit of screen time.

I found the start of the second half of the series massively disappointing: The Bells of St John was an enjoyable if slight runaround, but The Rings of Akhaten had almost no story at all, and Cold War’s story beats amount to “I will destroy the world” / “Please don’t” / “OK”. The next two episodes remain unwatched on my Freeview box hard drive – like I said at the start, when you’re a fan of something (TV show, football team, whatever) and it lets you down, the disappointment runs a bit deeper than just not enjoying the latest episode, match or what-have-you. That said, The Crimson Horror did an effective job of pastiching Hammer (notably, lower-budget and smaller-scale films than the rest of the series might have aspired to ape) and The Name of the Doctor was clearly the first part of a de facto trilogy with the two subsequent specials, so the series managed to claw back some ground by its end.

I’ve also struggled to warm to Clara. For plot purposes she was clearly meant to be a bit of an enigma prior to the season finale, but it did have the effect of making her seem a bit of a generic Moffat Who girl (though I don’t subscribe at all to the “Moffat can’t write women” nonsense – however bland Clara might be, it couldn’t be argued for instance that in Sherlock Mrs Hudson, Irene Adler, Donovan and Molly are the slightest bit interchangeable). In fairness, writing companions is extraordinarily hard: they have to have a certain set of characteristics (plucky, willing to run off into time and space etc.) and ever since 2005 it’s been hard to write them truly distinctively – probably only Donna Noble stands out as a bit different, chiefly because of her age and its implications, but certainly Rose and Martha were virtually interchangeable. It’s also not clear that having a companion who doesn’t actually travel with the Doctor really works. I liked the approach with Rory and Amy, allowing them periods travelling with him and periods not as their lives moved on, and the Doctor’s close bond with Amy allowed that to make a certain sense. But in what sense Clara is a current companion, other than that the Doctor keeps turning up to see her, is a bit of a mystery. Not a reflection on Jenna Coleman however, who has been consistently great in delivering the material she’s been given.

With a new Doctor and a full series on the way in 2014, there’s a bit of a sense of the programme regrouping after losing its way a bit. Possibly a completely unfair sense – and don’t get me wrong, I’m firmly of the view that Steven Moffat is one of the towering screenwriters in British TV history, to whom the show owes an enormous debt of gratitude – but that’s how it seems.

An Adventure In Space And Time

I was looking forward massively to An Adventure In Space And Time, which told the story of Doctor Who’s creation in 1963 and the tenure on the show of its first lead actor William Hartnell. And it didn’t disappoint – it was a lovely production, the one snag being that, as a Doctor Who anorak to begin with, I knew exactly what was going to happen. Nicely done though, including lovely location filming at TV Centre and recreation of the show’s original TARDIS set. The Matt Smith cameo at the end pulled me out of the story completely, unfortunately, but was compensated for by Reece Shearsmith’s cameo turn as Patrick Troughton: he didn’t look anything like the second Doctor, but caught Troughton’s air and mannerisms uncannily. It was a lovely addition to the anniversary celebrations though.

I was looking forward massively to An Adventure In Space And Time, which told the story of Doctor Who’s creation in 1963 and the tenure on the show of its first lead actor William Hartnell. And it didn’t disappoint – it was a lovely production, the one snag being that, as a Doctor Who anorak to begin with, I knew exactly what was going to happen. Nicely done though, including lovely location filming at TV Centre and recreation of the show’s original TARDIS set. The Matt Smith cameo at the end pulled me out of the story completely, unfortunately, but was compensated for by Reece Shearsmith’s cameo turn as Patrick Troughton: he didn’t look anything like the second Doctor, but caught Troughton’s air and mannerisms uncannily. It was a lovely addition to the anniversary celebrations though.

50th Anniversary Celebrations

It can’t be said that the BBC didn’t do the 50th anniversary justice, with various documentary programmes if different kinds – I doubt I’ll ever bring myself to watch the BBC3 efforts, and I’ve yet to get round to The Science of Doctor Who, but it was great to see them all get made. Again one I’ve yet to watch, but I gather the Doctor Who at the Proms celebration included an appearance from Dudley Simpson, the most prolific composer on the original show, and performances of some of his music, which was especially pleasing. My favourite of the many satellite programmes though was The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot, written and directed by Peter Davison and containing lots of wonderful fannish nods, not least David Troughton as a Dalek operator, alongside the real life voice of the Daleks Nick Briggs, and the revelation of John Barrowman’s greatest secret. The genuine bitterness subsequently expressed by Colin Baker regarding the non-appearance of most classic series Doctors (though I’m pretty sure I saw them all on-screen, quite cleverly incorporated via archive footage within its non-HD limitations if you ask me), but cameo by Tom Baker, in the anniversary special soured it a bit, by scraping the veneer of irony off it slightly. But never mind – all told, it was an imaginative, funny and affectionate piece.

It can’t be said that the BBC didn’t do the 50th anniversary justice, with various documentary programmes if different kinds – I doubt I’ll ever bring myself to watch the BBC3 efforts, and I’ve yet to get round to The Science of Doctor Who, but it was great to see them all get made. Again one I’ve yet to watch, but I gather the Doctor Who at the Proms celebration included an appearance from Dudley Simpson, the most prolific composer on the original show, and performances of some of his music, which was especially pleasing. My favourite of the many satellite programmes though was The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot, written and directed by Peter Davison and containing lots of wonderful fannish nods, not least David Troughton as a Dalek operator, alongside the real life voice of the Daleks Nick Briggs, and the revelation of John Barrowman’s greatest secret. The genuine bitterness subsequently expressed by Colin Baker regarding the non-appearance of most classic series Doctors (though I’m pretty sure I saw them all on-screen, quite cleverly incorporated via archive footage within its non-HD limitations if you ask me), but cameo by Tom Baker, in the anniversary special soured it a bit, by scraping the veneer of irony off it slightly. But never mind – all told, it was an imaginative, funny and affectionate piece.

Big Finish 50th anniversary stories

When the TV series hit its wobbly spell earlier in the year, I began particularly looking forward to Big Finish’s planned celebrations. Not only did they plan a full-on reunion story for all eight Doctors, but a companion set of three stories all set in 1963 featuring the fifth, sixth and seventh Doctors. In the event, the respective TV and audio adventures showed why the makers of the TV series get to play with pictures as well as sound: the first of the 1963 stories, Fanfare for the Common Men, was a fun runaround involving Peter Davison’s Doctor and a Liverpool band who aren’t quite the Beatles; Colin Baker’s outing, The Space Race, was an oddly-paced mess of Russian space exploration and talking animals, almost as if Andrew Cartmel had written it in the early 90s; and I haven’t picked up the seventh Doctor story yet – though as it reunites the main series with the excellent spin-off Counter Measures, I’m more optimistic. The anniversary story itself, however, The Light At The End, was the worst thing I’ve ever heard from Big Finish – so awful I gave up on it half-way through. The plot was a rambling, unimaginative mess, with a cartoonish Master setting some implausible trap or other for the Doctor – if nothing else, it showed just how hard it would be to do a full reunion of tons of Doctors on-screen, as plotting it must, in fairness, be almost impossible (the most the show has ever attempted in practice was four, with The Five Doctors in 1983 – Tom Baker got stuck in a time eddy or something, so things to do had to be found for only four of them). Worse still, the impersonations of the three deceased Doctors sounded nothing at all like them, despite the no doubt good intentions of all concerned – it was embarrassing. Who knows, maybe it gets really good in its second half, but I just couldn’t bear to hear any more of so much writing and acting talent being put to such poor use. The story was totally lacking the wit and imagination that Big Finish brings at its best – I wish it had been written by Alan Barnes…

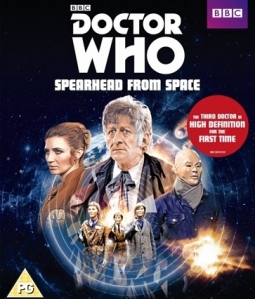

DVD releases

The original series of Doctor Who has been coming out on DVD for over a decade now, since well before the show’s return was announced. This year was to be the year in which the final releases came out. Because of the difficult nature of the archive holdings for Doctor Who – many black and white episodes missing, some colour episodes surviving only as black and white copies – the last few releases were the ‘difficult’ ones. Several black and white sixties serials that had an episode or two missing have had the gaps plugged with animations, while a few Jon Pertwee stories have been restored to full(ish) colour.

The original series of Doctor Who has been coming out on DVD for over a decade now, since well before the show’s return was announced. This year was to be the year in which the final releases came out. Because of the difficult nature of the archive holdings for Doctor Who – many black and white episodes missing, some colour episodes surviving only as black and white copies – the last few releases were the ‘difficult’ ones. Several black and white sixties serials that had an episode or two missing have had the gaps plugged with animations, while a few Jon Pertwee stories have been restored to full(ish) colour.

So the fiftieth anniversary saw the release of some long-awaited stories on DVD, though in truth they were long awaited because of their archival status more than their quality as drama, which was mixed. In the event, the last knockings of the DVD releases have spilled over into 2014, so not all are out yet, but the dedicated team who have worked for the last decade and more to restore the show for DVD and leave a legacy of high quality masters in the archive has, officially, finished its work.

My favourite release of the year, however, was the single high definition release of a classic Doctor Who story: all bar one of the show’s original serials was made partly or wholly using 405 or 625-line video, and so cannot be given a full HD release. Jon Pertwee’s debut, Spearhead from Space, was however shot entirely on film, and so has been polished up into HD and put out on BluRay. It’s a glimpse of what a more expensive, all-film, 60s or 70s Doctor Who might have looked like, and it looks great as well as being one of the high points of the original series (shop window dummies coming to life and bursting through the shop windows – that’s the one). The release was done on a shoestring as these things go, and we should be grateful to everyone who made it happen.

The missing episodes

It’s a complete coincidence that all this has happened in the anniversary year, but it’s still been – and promises to continue to be – massively exciting. Rumours of a major haul of missing British TV shows recovered from African stations grew strong early this year, and shot round the internet, mutating as they did so. I swung from utter scepticism to cautiously feeling there may be something to it, to disbelieving again. Finally in early autumn, things solidified and a consistent rumour of three Doctor Who returns emerged: Marco Polo, The Enemy of the World and The Web of Fear. And in October, the release on DVD was confirmed of… the second and third of those. The quizmaster in my pub quiz has a friend who claims to be well-connected, and had told me firmly that the announcement was on its way a couple of days before it emerged… he also reports that Marco Polo is now with iTunes ready to go on sale, its restoration having been delayed by technical troubles. We’ll see if that pans out. Certainly the BFI’s Dick Fiddy, speaking in the documentary screened at this year’s Missing Believed Wiped, seemed to confirm that there is indeed a big haul of stuff from Africa – although he rowed back from this firm position subsequently (but I was there and heard what he originally said, whether a mis-speak or not). It looks likely that there is therefore much material about to be returned to the archive, at least some of it likely to be Doctor Who. Will we really get the number of missing episodes down drastically? It’s a shame in some ways that the constant speculation is overshadowing the remarkable achievement of getting the missing total down below 100, which I certainly would not have expected twelve months ago. On its own, that’s a great bonus for the anniversary year.

It’s a complete coincidence that all this has happened in the anniversary year, but it’s still been – and promises to continue to be – massively exciting. Rumours of a major haul of missing British TV shows recovered from African stations grew strong early this year, and shot round the internet, mutating as they did so. I swung from utter scepticism to cautiously feeling there may be something to it, to disbelieving again. Finally in early autumn, things solidified and a consistent rumour of three Doctor Who returns emerged: Marco Polo, The Enemy of the World and The Web of Fear. And in October, the release on DVD was confirmed of… the second and third of those. The quizmaster in my pub quiz has a friend who claims to be well-connected, and had told me firmly that the announcement was on its way a couple of days before it emerged… he also reports that Marco Polo is now with iTunes ready to go on sale, its restoration having been delayed by technical troubles. We’ll see if that pans out. Certainly the BFI’s Dick Fiddy, speaking in the documentary screened at this year’s Missing Believed Wiped, seemed to confirm that there is indeed a big haul of stuff from Africa – although he rowed back from this firm position subsequently (but I was there and heard what he originally said, whether a mis-speak or not). It looks likely that there is therefore much material about to be returned to the archive, at least some of it likely to be Doctor Who. Will we really get the number of missing episodes down drastically? It’s a shame in some ways that the constant speculation is overshadowing the remarkable achievement of getting the missing total down below 100, which I certainly would not have expected twelve months ago. On its own, that’s a great bonus for the anniversary year.

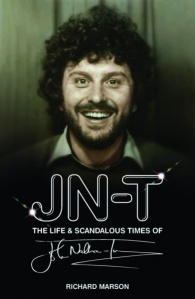

JN-T: The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner

Most aspects of Doctor Who have had at least one book written about them, and this extends to biographies of some of the key actors and personnel. This is probably the best of them all, and is a great piece of biography in its own right that should be of interest well beyond Doctor Who fandom.

Most aspects of Doctor Who have had at least one book written about them, and this extends to biographies of some of the key actors and personnel. This is probably the best of them all, and is a great piece of biography in its own right that should be of interest well beyond Doctor Who fandom.

John Nathan-Turner was the final producer of the original run of Doctor Who, overseeing it from Tom Baker’s final season all the way through to its cancellation at the end of the 80s. He was a complex man, and his story both fascinating and ultimately very sad. A rising star in BBC production, he saw himself as a potential future controller of BBC1, and many around him during his early career wouldn’t have seen that as crazy. His career stalled on Doctor Who, however: his first role as producer, in his early thirties, should have been a stepping stone on to other things; in the event, his near-constant efforts to move to or start other shows went nowhere, changing operational models at the BBC closed off future avenues as production was made a freelance business, and the increasingly troubled and ultimately failed production of Doctor Who dragged him down with it.

Richard Marson writes from the perspective of both a Doctor Who fan and a TV producer himself, having had a long stint at the helm of Blue Peter, also a long-running and sometimes flagship BBC show. He traces with authority both why JN-T was deeply loved by many who knew him, and deeply loathed by almost as many – both, as the book makes clear, with some good reasons. Certainly he rose to the limits of his incompetence: he had no understanding of drama, which hobbled the show throughout the decade as it put the whole onus for the creative direction of the show on the script editor (during the most successful periods in its original run, Doctor Who was guided creatively by a producer and script editor working closely together to develop the creative ideas underpinning the show – but JN-T just couldn’t fulfil this function, and worse still didn’t realise it). His frequent proposals for new shows were without exception gimmicky insubstantial rubbish, showing no grasp at all of how drama actually works. He was a highly able nuts-and-bolts man, however, and saw the programme made in the teeth of repeated production crises and eye-wateringly small budgets – no mean feat at all. Marson suggests, probably correctly, that he might have been a better light entertainment producer, or in a salesman / promoter type role for for the show globally – he was an instinctive showman, that much is clear.

JN-T’s personal life is also rightly prominent in the book, though never salaciously or in any way not justified by events. He was a promiscuous gay man who enjoyed contact with young men – plenty of whom came his way given the nature of the Doctor Who fanbase. Had he still been alive, there can be little doubt that he would have been dragged into the post-Saville swirl of retrospective scandal around the BBC; as it was, one or two tabloids picked up on the contents of this book and ran with it long enough to drag Colin Baker in, totally unfairly, but the story inevitably went nowhere. Throughout nearly all his adult life however, JN-T was in a devoted relationship with long-term partner Gary Downie – an association that Marson suggests might have harmed his career, as Downie was a difficult customer prone to rubbing people up the wrong way in every possible sense.

JN-T died aged 54 in sad circumstances; I won’t go on any further – just buy the book. I came away from it not particularly admiring John Nathan-Turner, but certainly liking him.